Rock Climbing: Injuries and the importance of rehabilitation

Rock climbing is becoming increasingly popular throughout the world with an ever increasing variety of disciplines and participants. From urban indoor settings to natural boulders and crags, the enthusiasm for climbing and it’s accessibility is making it one of the hottest sports of the last decade, especially after it debuted as an Olympic sport in Tokyo 2020.

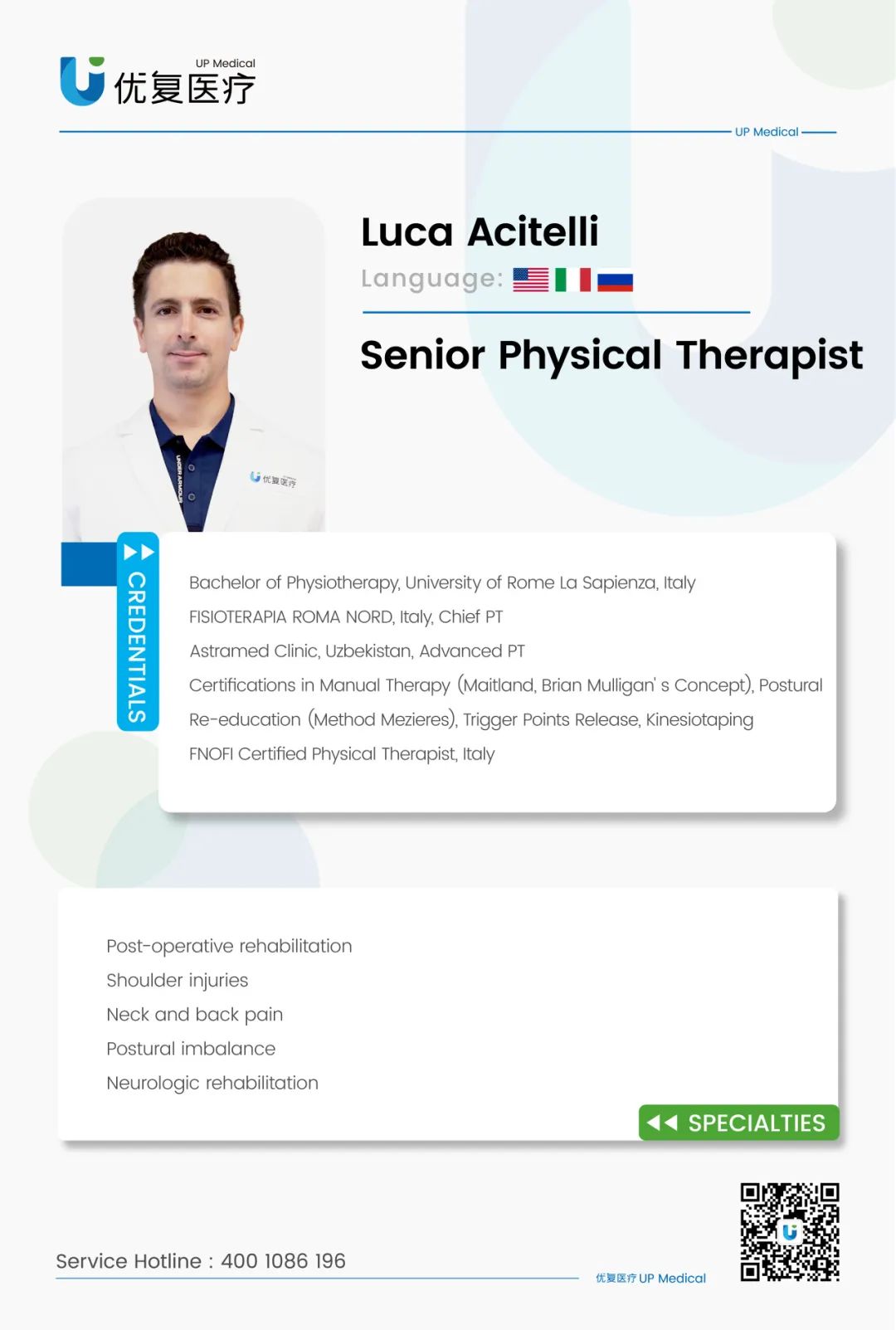

Author / Luca

UP Medical

In Shanghai city there are approximately 16 rock climbing gyms, ranging from larger climbs that incorporate harnesses and bouldering, to short walls with no harness necessary. Some are very easy to access as well, including the structure located on the West Bund, which is completely free and accessible to anyone who desires to try this amazing activity. While this activity can quickly turn into a passion, it is worth understanding safety considerations, and if and when injuries do occur, how to effectively rehabilitate them.

It’s important to first address several different arenas of sport climbing:

1. A route with a wall height of more than 15 ft.

2. Bouldering with a height between 9 and 15 ft.

3. Speed climbing, which is about 49 ft.

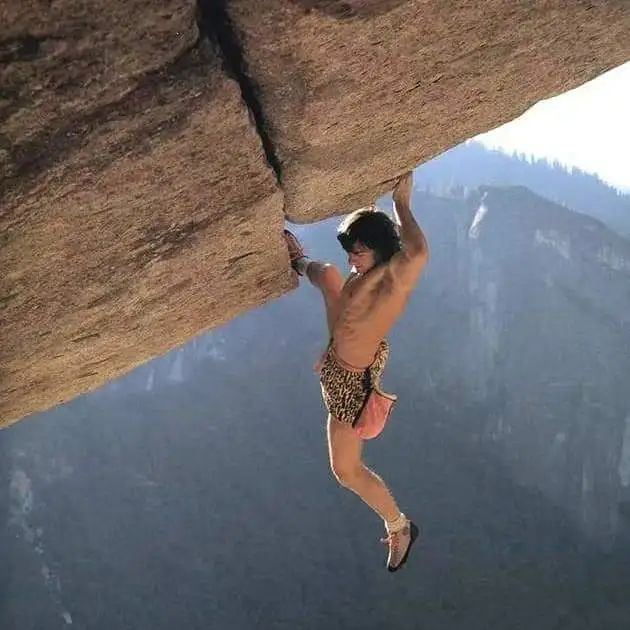

These different types of climbing can fall under the category of ‘sport climbing’ if the progression takes into account special bolts already present on the rock, and if there is a “top rope”, meaning if the help of the rope comes from above. In traditional climbing, removable cams are put inside the rock-cracks to ensure the ascent, whereas in “free-solo” there is no safety system and the climber’s life depends only on his physical skills and cool blood…

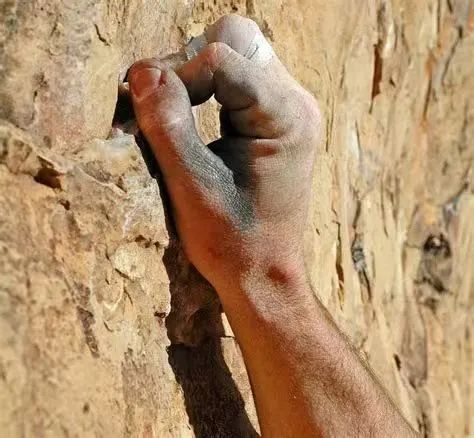

Grips can range in variety, as well as the techniques and biomechanical scheme that follow. The full/closed crimps are the most stressful for the finger pulley, especially on the indoor holds, less ergonomic and more acute-shaped than the natural ones. ”Lock-off”, “Sideways Flag”, “Reverse Outside Flag” and “High Step” are some techniques widely used to better fight gravity and imply the synergic activation of upper extremities, core and lower body muscles.

Now that we’ve discussed the different types of climbing and features, it’s important to understand how if you participate in this sport regularly, you might be susceptible to pain or injury. Statistically speaking, the most common parts of the body prone to injury are the: fingers, shoulders, hands, forearms and elbows. Other upper extremities and the spine/trunk can also be prone to injury, although the instances are less common. With these parts of the body, among the most frequent types of injuries are: pulley problems, tendinitis, joint instability and muscle strain, which is very common in the finger flexor tendon.

Shoulder pain is often a big complaint of climbers, which can be aggravated by overhead far reaches or being in a ‘locks-off’ position on vertical routes because it can significantly increase the stress on the joint (ex: SLAP tear, capsulitis, tenosynovitis). Similarly, elbow pain commonly occurs because of the progression posture: the overuse of crimps, ‘chicken wings’ in the shoulder and gripping with an extended wrist that can lead to overload, especially in the lateral part of the elbow (lateral epicondylitis).

Another concern for climbers is a pulley sprain of the finger. Pulley’s are a complex system of cartilage arches whose function is to stabilize the flexor tendons. They get injured secondary to the high levels of forces placed on them during crimping, especially during the eccentric crimp grip, with a mechanism often associated to an audible ‘pop’. For example, the A2 and A4 pulleys have the highest risk of breaking because they are less deformable. Did you know that they can be loaded with forces that can reach an incredible average of 54 kg!?

When being treated for pain from climbing our ‘rock rehabilitation pyramid’ is based on the following steps applied progressively: UNLOAD, MOBILITY, STRENGTH, MOVEMENT.

Injuries can be managed within a framework by unloading the tissue, increasing mobility, improving strength and returning the climber back to pain-free movement. Each parameter is assessed by the provider with clinical tests/measures and through climbing movement patterns. Rehabilitation in climbing, like in other sports, means also prevention and it should be integrated into the sport routine. Several studies have reported that if there is a limitation or poor quality in movement patterns, this can affect negatively the performance and put the athlete at higher risk of injury. Screening the individual for restoring proper movement and identifying a possible pathology in the body is key.

Some of the best practices of physiotherapy in rock climbing include:

1. Kinesio Taping, Rigid Strap and Taping. If used properly taping helps to unload key joints both for rehabilitation purpose and prevention. As an example, we can take the “H-Taping” for finger(s), which reduces tendon–bone distance by 16% and increases strength in the crimp grip position by 13%.

2. Mobility/Motor control. This intervention is targeted to improve the mobility and coordination depending on the type of problem. A complete range of motion for the joints is necessary for an efficient level of body control and the development of strength, which in turn enhances climbing performance.

3. Anterior Trunk Sling Strength. The core is a group of muscles that stabilizes and controls the pelvis and spine (and therefore influences the upper body and the legs). Core strength is less about power and more about the subtleties of being able to maintain the body in ideal postures — to unload the joints and promote ease of movement. Being able to dissociate the trunk from the upper and lower body and keep a good anterior reach not only facilitates the rehabilitation process but also prevents from overuse, thus easing the climbing movements.

4. Plyometrics/Impact. Plyometrics and practicing impact are important aspects, especially in professional climbers who attend competitions. They involve rapid muscle stretching and contraction in order to increase power production. For a climber, this means the ability for them to move quickly off of a hold with a large amount of force, exploiting the recycled energy.

5. Posture Alignment. Good body posture and quality of functional movements is an essential condition for improving activity level and decreasing the risk of future injuries.

“As a Physical Therapist at UP Clinic and a rock-climbing enthusiast, I can help you not only recover from climbing-related injuries, but also teach you how to integrate high level exercises with the goal to improve your performance and safety in the climbing environment. It does not matter if you are a veteran of this sport or are just beginning. Prevention is more important than ‘fixing a problem’ and starting physiotherapy at the beginning of your climbing journey can make a difference. It allows you to enhance your skills, reduce the trauma risk and focus better on long-term goals.”

By: Luca Acitelli PT

本篇文章来源于微信公众号: 上海优复康复医学门诊部